#0003: Change is difficult. Or...is it?

Challenge change while you challenge yourself. Connect with others to thrive.

There are multitudes of ways to cope with change, yet the cliché “change is hard” endures. Ask ChatGPT ‘why is change hard for humans’ like I just did, and a friendly neighborhood AI happily provides an explanation (bold / italics are my addition):

Change can be hard for humans due to various reasons:

Comfort zone: Humans are creatures of habit, and they often find comfort in familiar routines and environments. Change disrupts this comfort zone and introduces uncertainty and unfamiliarity, which can be unsettling and stressful.

Fear of the unknown: Change often involves stepping into the unknown, which can trigger fear and anxiety. Humans tend to prefer stability and predictability, as it provides a sense of security. The uncertainty associated with change can evoke concerns about potential risks and negative outcomes.

Loss of control: Change can make individuals feel a loss of control over their circumstances. When things change, they may no longer have the same level of influence or familiarity, leading to a sense of powerlessness or vulnerability.

Cognitive biases: Humans are subject to various cognitive biases, such as the status quo bias and confirmation bias, which can make them resistant to change. These biases incline individuals to stick with what is familiar and to seek information that confirms their existing beliefs, making it challenging to embrace new ideas or perspectives.

Emotional attachment: Humans develop emotional attachments to people, places, and routines. Change often involves letting go of the familiar, which can result in feelings of loss, sadness, or nostalgia. Breaking attachments and adapting to new circumstances can be emotionally demanding.

Effort and discomfort: Change typically requires effort, energy, and stepping out of one's comfort zone. It may involve learning new skills, adjusting behaviors, or adapting to different circumstances. The discomfort and effort involved in change can deter individuals from actively pursuing or embracing it.

Social pressure and norms: Humans are social beings who are influenced by their social environment. Social norms and peer pressure can discourage individuals from embracing change if it is perceived as deviating from the group or going against established norms.

While change can be challenging, humans are also capable of adapting and growing. With the right mindset, support, and strategies, individuals can overcome the difficulties associated with change and navigate through it successfully.

What do we extract, learn, hopefully simplify, and then apply from this informative download compiled by an AI assistant armed with a supersaturated language model? So many things, first of which is that ChatGPT has access to a massive data set and a PhD-level understanding1 of humans and neurochemical brain pathway research. If AI hasn’t helped you yet, it will, just go ahead and ask it a question. Knowing how to work with AIs and similar systems is going to be a popular skill, and they are going to show up in absolutely every corner of modern life. I suggest you prepare yourself. In terms of what it spits out, it only took about 15 seconds to generate an answer. Congrats, we just saved $100k and four years on postgrad school! Higher education couponing aside, there are actual physiologists, biochemists, and neurologists who have collectively researched, experimented, theorized, and postulated for decades to discover and map the brain-behavior patterns that AI regurgitates in seconds. We should take a moment to recognize and appreciate the body of work required for this innovation to be available at our fingertips. Thanks, grandpa!2

This depth of understanding baked into cutting edge processing and relational models is wiki-ed fast and provides a sound basis for extrapolating why change is difficult. Technical marvel aside, let’s double click on what is and is not included so we may unpack and develop a few methods for handling change gracefully. By “handling”, I do not mean “coping”, although that is also an interesting branch from this conversation.

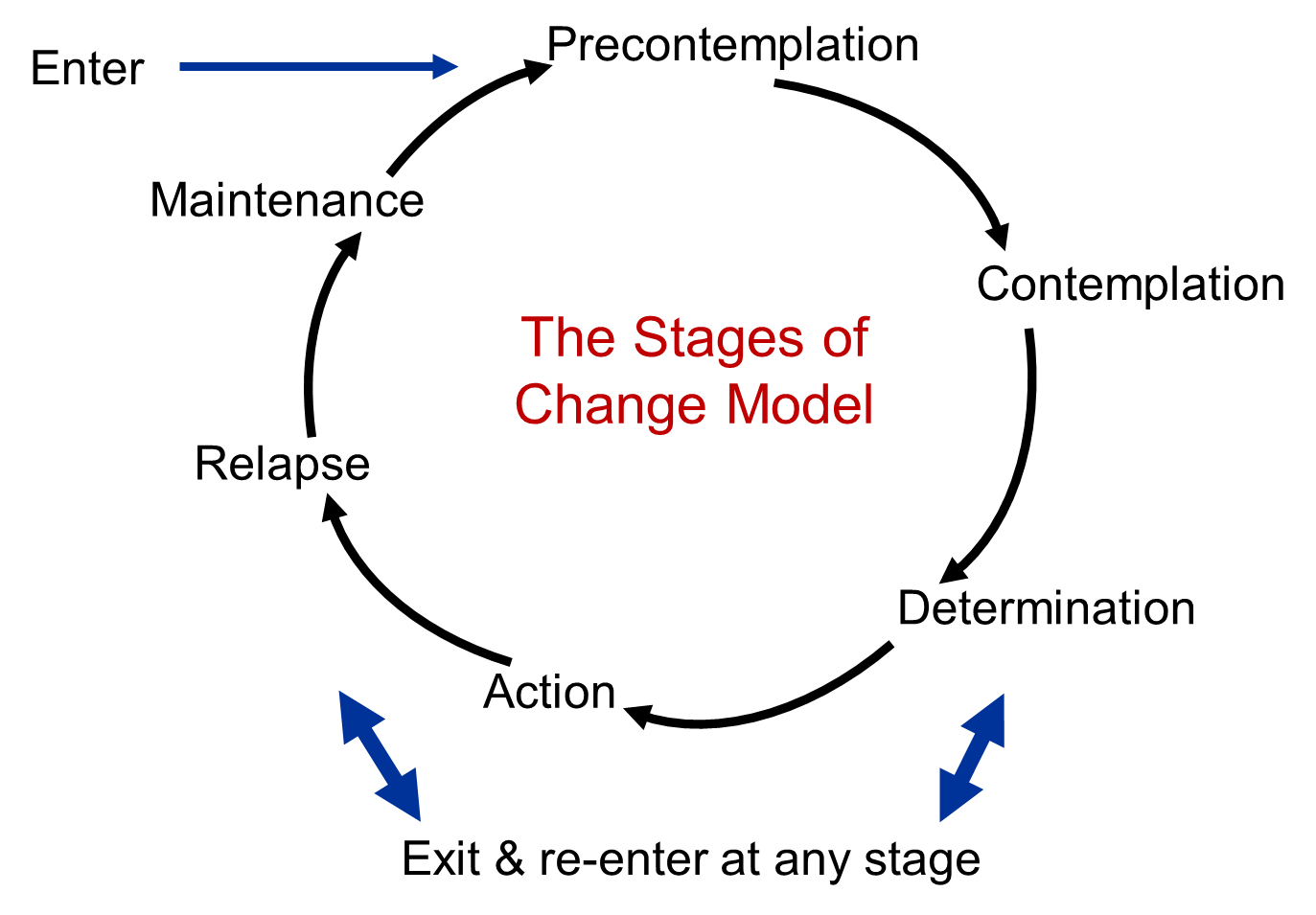

“Handling” means interrogating, understanding, emotionally separating, objectively processing, deciding, and activating a course of action. There is a thing out there called the Transtheoretical Model (TTM)3 which describes stages of change in humans. This model may come in handy for figuring out how can we be successful in facilitating change based on what someone is experiencing during change.

It is useful for this examination (and in any professional role, whether individual contributor or people leader) to have a layman’s understanding of how change is processed internally and individually. The obvious reason being, if you can identify where someone is stuck4, it is far easier to connect with them to support change progression.

“Gracefully” requires accomplishing a desired transformation without any scorched earth, burned bridges, or latent harbored feelings of necessary retaliation. Having experienced all of these myself, you just have to trust me on this one, it falls into the Schmidt category of ‘do not want’. Change itself is not a difficult concept; why is it so paralyzing for so many? All we are really talking about is catalyzing a specified <thing> from one state to an immediately adjacent state, or through a series of adjacently adjoined states to a desired state. The idea itself is simple - start point, delta, goal. In the TTM diagram above, a lot of cycle time - half or so - is taken up by the thinky part of the brain (neocortex for you brainiacs out there) processing “what is this thing”. What if there was a way to fast track that part, or to help reach the determination understanding more quickly and easily? Hmm…

Let’s say you are working with a group on a big change, perhaps something concerning modification to work schedules or contract terms. Something that really impacts people in their daily lives. Carefully crafted and communicated, everyone has been informed of the change requirements. Via your intuition and / or unspoken cues - facial expressions, body language, grubmbly noises, murmured expletives, hurled cabbage - you observe some (many...possibly most) of the affected hanging out emotionally somewhere (you surmise) between precontemplation and determination. Sorry to inform you…that’s not quite where they are thinking-wise at this stage. What is actually happening “under the lid” when someone is first presented with this kind of stressful information is not addressed by our TTM response model at all. Several other models5 wax poetic and scientific about how / why / when humans transition from stimulus input to response, with the bottom line here being: If you want someone to engage with a change instead of run from it, you will need to figure out how to get past the sympathetic nervous system response to the message you just delivered. Right now, in their minds, the turd you just chucked at them is being physiologically processed identically to a threat response. In their PUEP (Personal Upstairs Emotions Processor, not a thing, just made it up), this is the equivalent of literally being attacked by a lion. The bit of their brain that you want access to for change integration has been isolated out of the picture by the amygdala, aka lizard brain. This matters a lot, because this response controller commands about twice as much bandwidth and access to make the body do things (via the thalamus - where the instructions to your body are routed) than the cortex (the thinky part) enjoys. It seems silly on paper that this would be the case, but the design makes sense - we have evolved this way over millennia to actually process threats, and we have not yet evolved special “PowerPoint bypass” biochemical adaptations to avoid a 4F6 response.

The water turns murky and gets deep fast when homosapiens, their feelings, and their emotional baggage aka previous adventures become entangled with simple, beautiful change. The mortal experience does more to challenge and block change acceptance than any outside force due to <all the reasons described at the top and in the last paragraph>, and much like every parent has heard from their 3-year-old when presented with a set of options they do not like, “NO!!!” comes next. The port of cooperation slams shut with a resonant thud, accompanied by a thunderous chorus of “YOU CAN’T MAKE ME!”. If that proclamation is true or not is irrelevant; what matters is that the rock-hard-place-nope-not-moving-from-this-spot buttress is definitely not the neighborhood to hang out in if you aim to create motion in the desired direction. Often, we are not fully aware that we are entering danger territory until it is too late, and the precious resources we are so vigilantly seeking (namely time and attention) are securely locked behind the Gates of Mordor. The slam of the great bar echoes behind us, and we realize (too late) we are now trapped in the swamp of Fear of the Unknown. Or maybe it is perhaps the barren salt desert of Wasted Effort and Discomfort. Whatever crap place you are in now, it’s a pin on the navigational map of life that was not on your bucket list. If Yelp only had a zero stars option…

Another cliché comes in handy here. Something about, “an ounce of prevention is worth a pound of…yada yada something bad.” Basically, before you introduce what could be a difficult, controversial, or dynamical7 change or series of changes, take a bit of time to plan. 5-P's comes to mind: Proper Planning Prevents Poor Performance. Some have a 6th "P", but it feels as if there are enough "P" in this conversation. While it is true that no good plan survives first contact with the enemy (or change in this case, despite appearances your colleagues are truly not enemies), the value gained is in the planning process itself. Although they may not feel it at first, allocating adequate time to plan important changes shows deep respect for the audience. A planning process creates space to put on and wear the hat of the recipient, visualizing how you might feel about the information were it headed your own way. See it through different eyes. You can organize ideas around why the change is necessary or valuable, and focus on making the data transparent that supports the objective. Whether or not you have positional authority, aim for creating messaging that enlists, inspires, engages, uplifts:

We will go do these awesome things together! Combined, we accomplish more than our sum.

Rather than defeats, deflects, dilutes, destructs:

You have to do it because I said so. Bah humbug. Don’t ask silly questions.

Before delivering to the intended audience, dry run with someone willing to really try to get into the shoes of the affected and give feedback on how it sounds and feels. To borrow from the legend Maya Angelou,

“People will forget what you said, people will forget what you did, but people will never forget how you made them feel.”

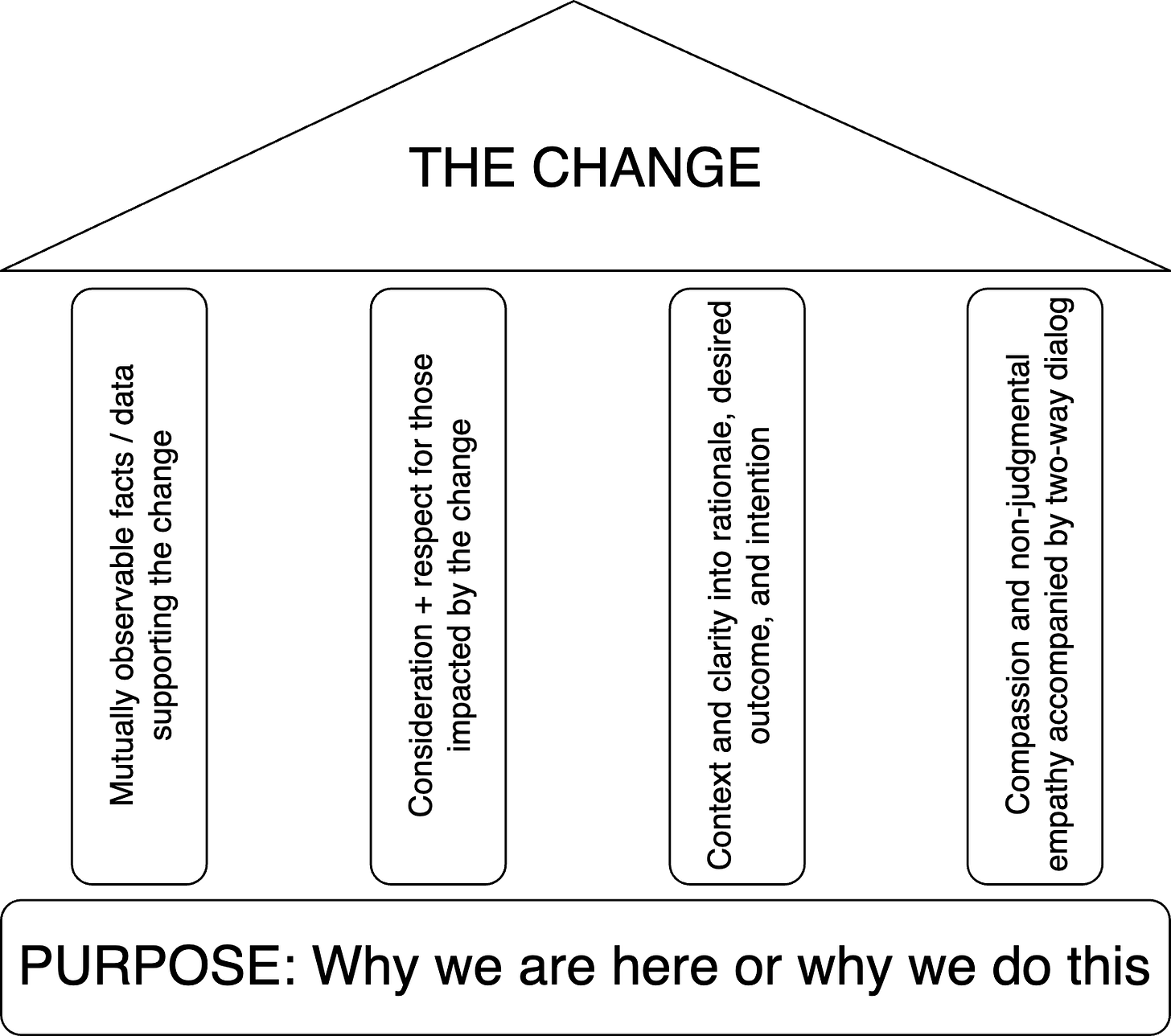

Even if you do this you will certainly not anticipate *all* feedback, but you are likely to catch important ideas that would otherwise be missed. You can then include them up front, demonstrating additional respect for your assemblage. The basic model for success is:

Know why the change is needed.

Care about how your audience feels about the change.

Share why it is required, supported by mutually observable facts.

Add context to support transparency and make room for dialog.

Be clear and candid about how it supports purpose.

Transparency and timing are critical throughout the process, as you will need to feed information back and forth throughout any transformation to clarify, adapt, and advance towards the goal of successful outcomes. If there are negotiations involved, keep in mind that positional leverage is NOT the way to go here, you must embrace the idea that negotiation = a furtherance of both parties’ goals8. A note on transparency: This does not mean 100% access to all information. It means providing the context for the decision and changes that are required. There is a non-trivial amount of work and preparation involved in big changes, so here's another novel idea: Make the changes smaller. Learn about and follow the Kaizen Way. Changes do not need to be large in nature to deliver big in result; there is no geometric or statistical relationship between change size and change benefit. At the end of the day, what you are aiming to accomplish is traction against the 7 reasons that make change hard. For each of the reasons that may rear its ugly head in your reality, here are some techniques you can use to combat the difficulties, or at minimum soften them up:

Get your audience past the emotional reaction to a change.

Engage with them to support their internal decision cycle. Push them out of their comfort zone, but with the assurance that you are there to support and help them grow. Ask good questions like, “why do you think that?” if faced with remarks like “this change is bad.”. Put on your Zen hat and seek to understand their perspective with active listening, empathy, and gratitude for their willingness to share. If you are incentivizing a change, no matter what you are offering, be prepared to hear feedback like “that is not enough” regardless of the scope / size / inconvenience of the action. Seek to include non-monetary compensation such as learning, development, additional opportunities to be successful and grow, or the anti-incentive of what negative consequences may befall everyone if changes are not adopted. No one wants to become obsolete. Avoid any doom-and-gloom fear tactics, just be honest about what keeps you up worrying at night.

Make the unknown, known.

Connect with anyone impacted by the change and create psychologically safe space to have conversations about whatever the audience feel the need to discuss. This is often as easy as saying, “this is safe space”. To make that real and trustworthy you also have to practice putting your own bioreactions in check and chucking any ego out the window. If this is a large organization, ensure you deputize those willing to take a lead role in conversations. Enable parallel conversations on behalf of the group, and spend time with these like-minded individuals to practice how to discuss the hot topics the same way.

Support their process with mutually observable facts.

Allow for productive dialog so they can feel more a part of the conversation; help them be a driver rather than just along for the ride. If they react poorly to the initial news, fear not - things are almost always salvageable. Depending on which first three “F’s” they present (Fight, Flee, Freeze, I would hope not to see “Fawning” in this context), you may want to try the following:

Fight: If you are greeted with animosity, anger, or hostility, seek to understand the source. Anger is not itself a primary emotion, it is always secondary to something else. It is a useful road marker to dig into what is really going on. Use your genuine questions to discover the primary emotion, allowing reasonable time and space if necessary. When someone is upset they may have a difficult time listening. Allow for a cooling off period prior to discussion. Then, invite the conversation, do not mandate it. No one likes feeling upset. The majority of time, an olive branch will bridge the gap.

Flee: Depending on the flight vector (retreating to an internal closed off place, literally creating distance including avoidance, vanishing entirely), a couple of things may work:

Put a “when you are ready” open invitation out to seek an audience, and offer a safe space guarantee with no constraints. Be willing to hear something you do not want to hear, take time to process it, respond calmly.

Omnichannel communications are available, but you should not have to chase anyone. Try to understand their personal situation and how they prefer to be communicated with. Why might they be using this tact to dodge a conversation? Set a reasonable time box for comment and feedback; help shepherd and create the boundary between “you have time to process this as you need” and “this is moving forward, please engage.".

In a professional situation, if someone vanishes entirely, that typically falls under job abandonment. Your local laws apply so check those first, but in most places here in the US, that is a terminable offense. Perhaps not the outcome you want, but possibly the one you need for a ghost.

Cognitive bias is real, and skepticism is healthy.

Take the feedback and answer questions transparently. Cynicism is toxic to any group, step on it if it pops up and explain why in plain terms. One strike rule the first time it happens, if someone is honestly unclear on why that kind of behavior is not acceptable in a professional situation, this is almost always addressed by a corporate code of conduct or employee handbook. A second or third instance constitutes a pattern. Coming from personal experience, no one needs to be unprofessional or launch personal attacks, but some people let their emotions get the better of them. Worst case, an individual just do not acknowledge why basic rules of courtesy and conduct apply to them. If they are in this camp, you have a different problem on your hands related to culture, the change itself is not your most pressing issue. Cynicism extorts progress and will impede success unless you can get it surfaced and solved.

Emotions are triggered by perceived change, even when it is for the better.

Where possible. make changes digestible and atomic, and demonstrate to your audience how transformation works and is superior to current state. The evolutionary ladder is full of dead-end branches; don’t let your group become one.

Change requires energy input.

In exchange for stepping out of one’s comfort zone to participate, you can offer new skills or circumstances which present an upside. Most things worth doing are hard and require some level of struggle. This is how we learn and grow.

Get a couple potential influencers over the line first.

You only need a few voices in the group to be early adopters. Convincing three people to fully embrace and evangelize a change is better than a dozen unsures or non-committal halfways. See #4. You may be surprised to find those very same skeptics from #4 will be the greatest advocates for advancing change once their questions are answered and they feel like they are a driving force of progress.

If all else fails and you cannot show why the change is a good thing, should you do it? Would you want to be subjected to a change like that if you were on the receiving end? Ask yourself the hard question. Often, you can avoid adverse situations entirely by making a no-decision decision (do nothing intentionally), or just not making the change that is proposed. Should you find yourself in the unenviable situation of not being able to pursue a change deliberately and with forethought, is it really that important? If the change itself has not been prioritized near the top of whatever overarching planning process exists, it is unlikely to be successful. Not all changes are good ideas. You should not make any blanket assumptions that because it has been said, it must be done. Alternatively, consider delaying or scoping down to reduce the risks involved. Each interaction should be approach with time and respect to proceed smoothly. If you do not have or allow for adequate time (and the harsh reality is, some situations do not have this luxury), be prepared for a bumpy ride. Run through best case, most likely / mid-range, and worst case scenarios to understand the margin of “good” and “bad” you are working with. Even in a worst-case scenario, you probably will not create a catastrophe, and in a best case scenario, the outcome may land around 60% of what you aimed for. Feel good if you leave the situation better than you found it, you have accomplished a challenging milestone.

Sorry for no secret answers, as most of what we have discussed is just a rigorous application of common sense. Let this wisdom be your guide, since common sense is anything but common. Actually - there is one secret answer - if you can learn the sacred mystical skill of inception, whereby stakeholders become the agents of change simply because you have had the foresight to build it into their psyche far ahead of time, presto. You have just created change magic. Bottle this, and sell it. I’ll buy some.

Using the term “understanding” for an AI is technically inaccurate, I am using it here to refer to the data itself rather than diving into relational large language models. All of the “understanding” output from an AI is knowledge that a human created patterns for.

My grandfather (Robert J. Rutman, PhD) taught biochemistry at University of Pennsylvania for over three decades. For accuracy, I should mention his work primarily focused on cancer research rather than brain stuff.

I have not yet read “Changing for Good” by James O. Prochaska, John Norcross , and Carlo DiClemente, or “Changing to Thrive” by James O. Prochaska, and Janice M. Prochaska, but both appear to be very good based on colleague feedback and reviews. I am not an Amazon affiliate at this point so I have not provided links, I may try that “buy my stuff” things later.

This applies if they are actually stopped, and not simply still processing. It can take some experience to figure this out in real time. When in doubt, give them a minute, would ya?

Great summary here: https://www.verywellmind.com/theories-of-emotion-2795717

The 4-Fs: Fighting, Fleeing, Freezing, and…Boning. Currently the 4th “F” is “fawning” but when I was growing up and learning this stuff it was the *other* F word.

From “Three Kinds of Change” blog found on hsdinstitute.org

Two great books on this topic are “Getting Past No” by William Ury and “Getting To Yes” by Roger Fisher, William L. Ury, Bruce Patton.